Luis Mendo draws from a tiny studio in Tokyo and is the creative director at Almost Perfect. He can be found at his website, at his alter ego’s website, on Instagram and Twitter, and through his newsletter.

Hi, Luis. You are a Spanish art director and illustrator working in Tokyo. Can you tell me a little about your background?

I was born in Salamanca in the late 60s – that is quite relevant, I like to say it (laughs). I’ve always worked in graphics – in school, I studied graphic design and illustration. When I had to specialise, I went to Madrid to do illustration.

But halfway through the year I didn’t like the teacher and I thought, «What am I doing here? I’m changing to design». So I moved back to design until the end. Shortly after graduating, I worked as a designer in Barcelona for a bit and then in the Netherlands for years.

I’ve worked a lot developing magazines. I would start them – a publisher would come along, wanting to start a magazine or a newspaper, and I would set up all the fonts, the art direction guidelines, and leave the production to the design team. I did that for years. The Netherlands is a small place, there weren’t many people doing such specialized work, so in the end everyone knew me – it was easy, like being a one-trick pony, but one of the best one-trick ponies in the world, or at least in the Netherlands. I had my one trick, I did it very well, and when they said «jump», I jumped. But of course in the end I had been asked to jump so often that I was completely burnt out.

And then my father died. You could say too much work killed him, and I realised that I was doing essentially the same thing. So I thought, «I’m going to take a three-month sabbatical. I’ll go to Japan, I’ll go to Tokyo. I don’t know anyone there, I don’t know Japan. I only know Mazinger-Z and that they use chopsticks to eat». So I came to Japan, and I loved it. But I already had a life in the Netherlands, and it took me four years from the first time I came until I finally settled here, four years going to and fro. And now I’ve been here for almost ten years.

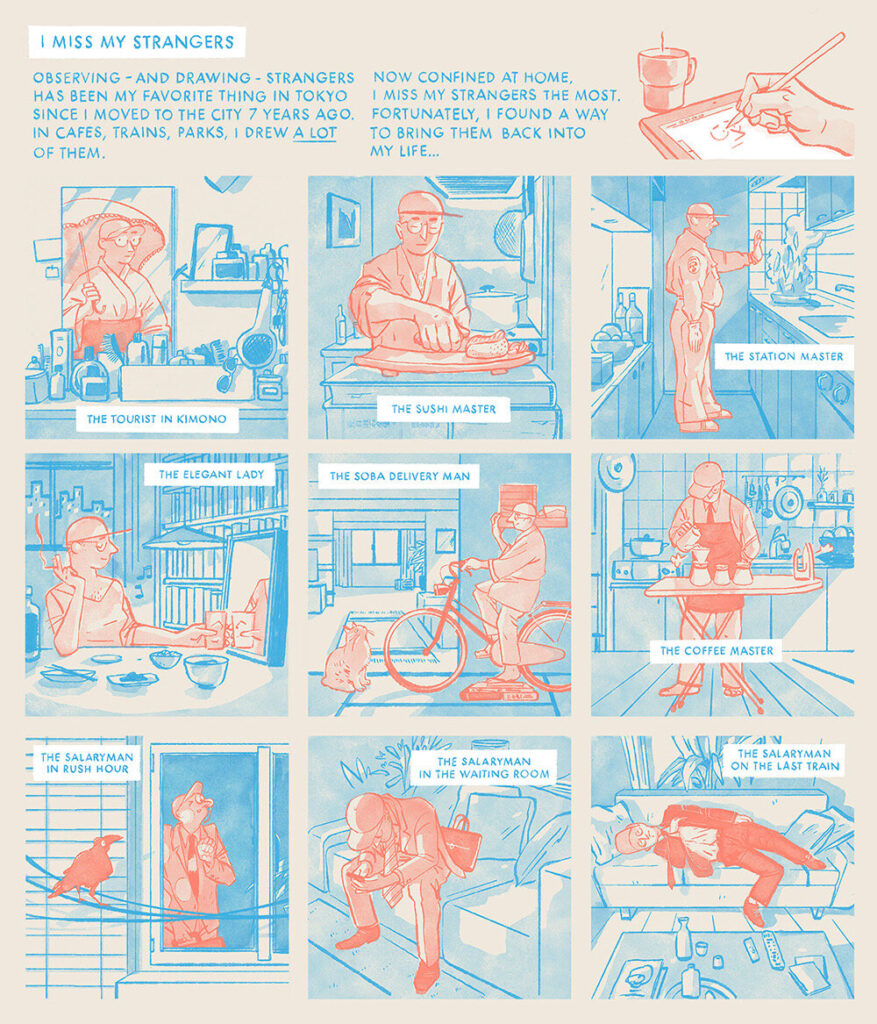

When I arrived I was an art director and I couldn’t work as one in Japan, because I didn’t speak Japanese and I could’t manage illustrators and photographers or talk to journalists and so on. And I was completely burned out anyway, so I didn’t even think of starting to do the same work here. Instead, I would just spend my time in cafés, drawing with a new friend. And after five or six months my friend said, «Hey, why don’t you become an illustrator?» I said, «No, I’m really bad at it, I just draw to amuse myself, I have no ambition whatsoever».

But she said «No, go to my agent». I went there almost as a lark, but they said «this is great.» I thought they wouldn’t call, but one week later they called offering me the first job, then another one and another one. And then some of my former colleagues, who were art directors and had heard that I was drawing now, called to ask «hey, why don’t you draw for us?»

That’s how I got to work for De Volkskrant, which is a major Amsterdam newspaper, doing the travel section. And little by little the thing grew, like snow accumulating.

Like a snow ball.

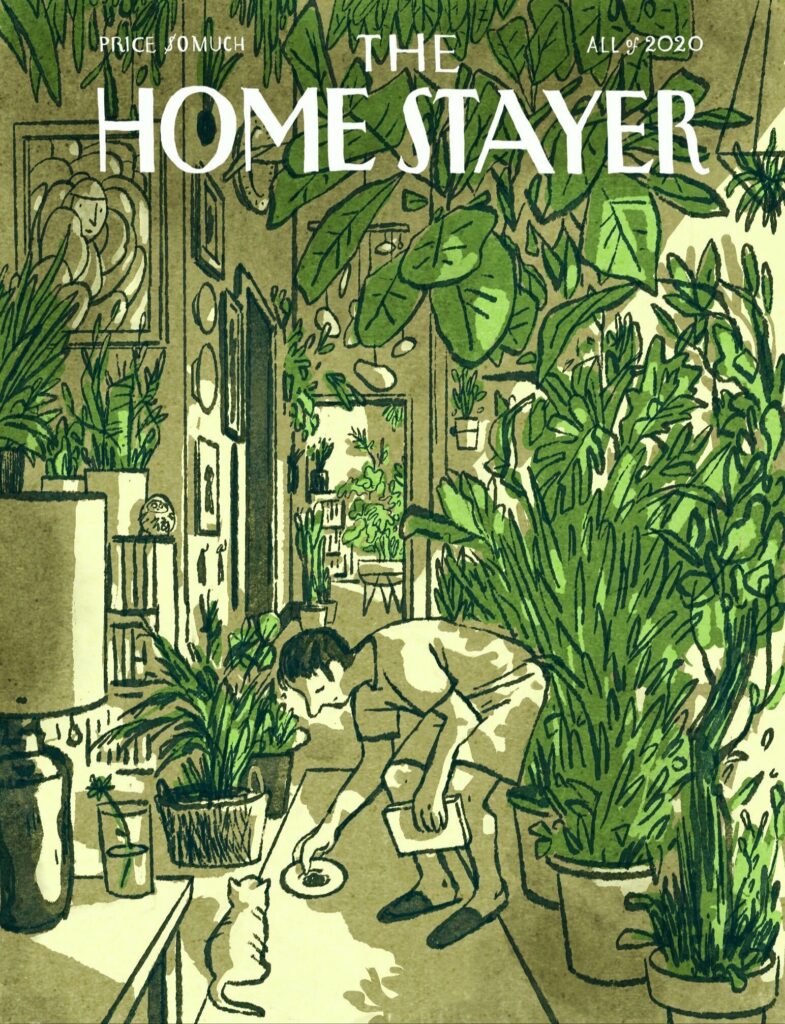

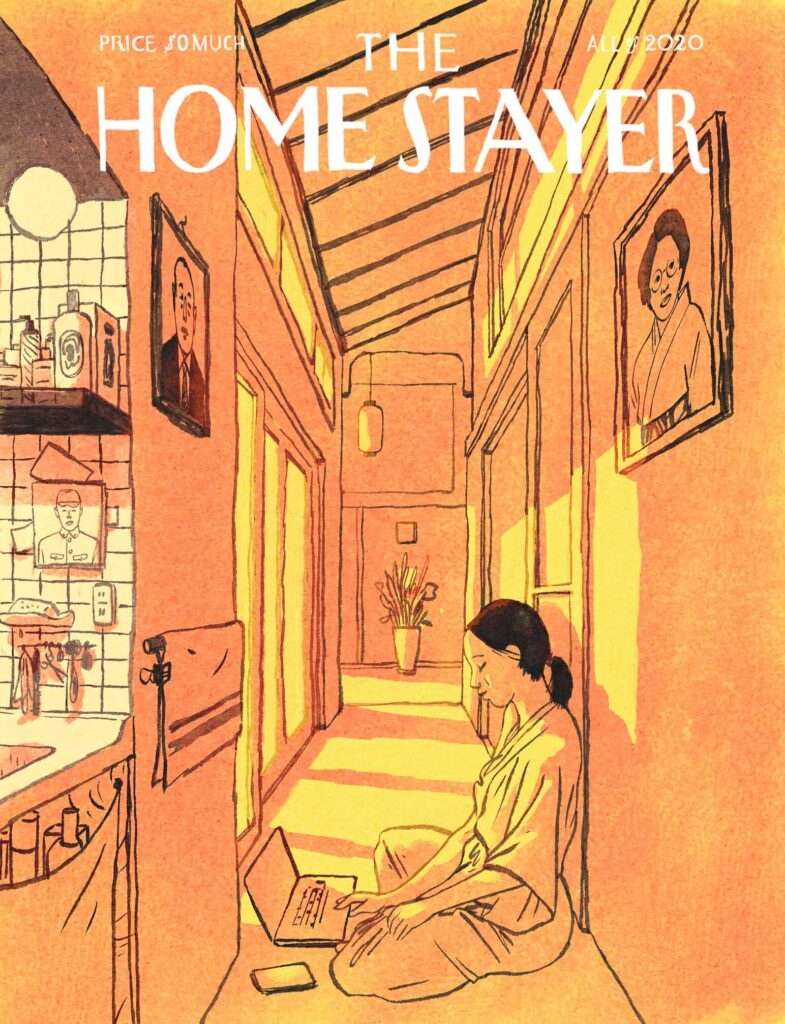

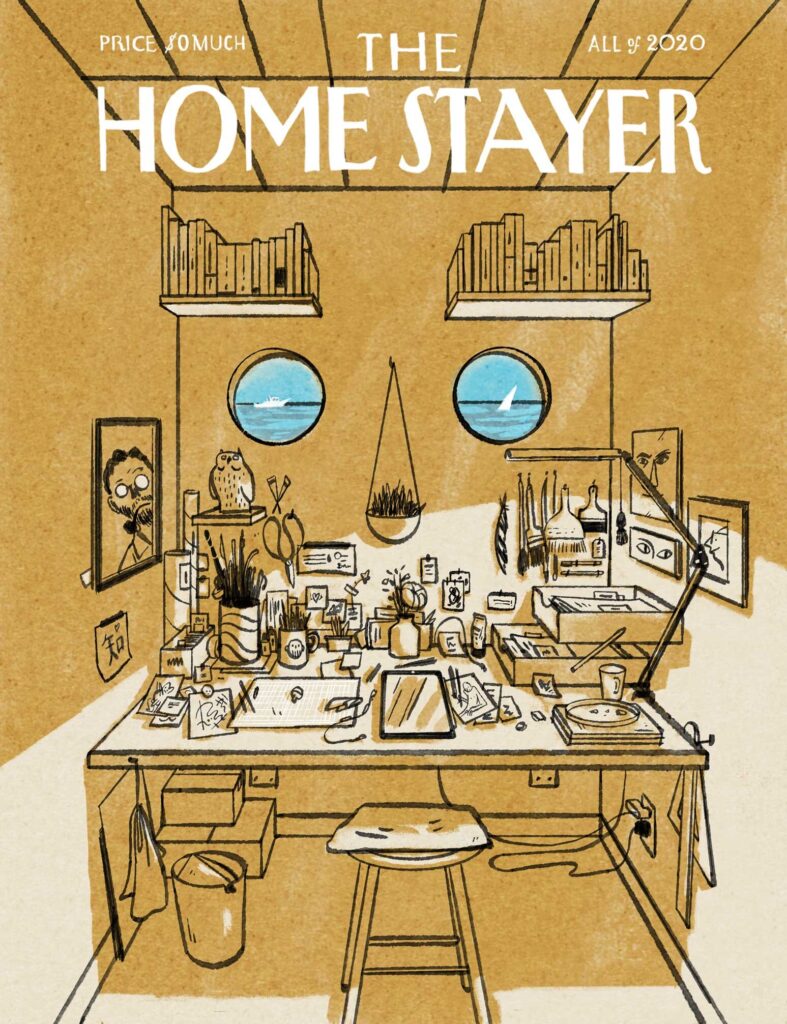

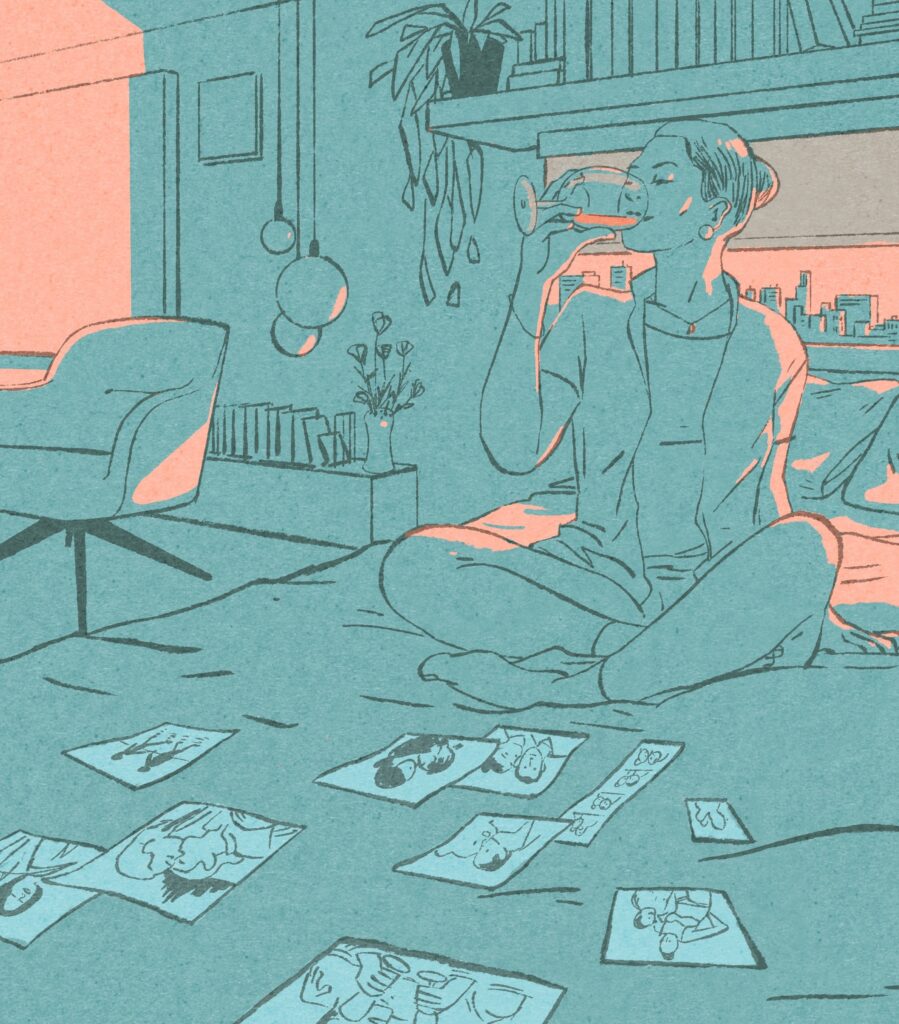

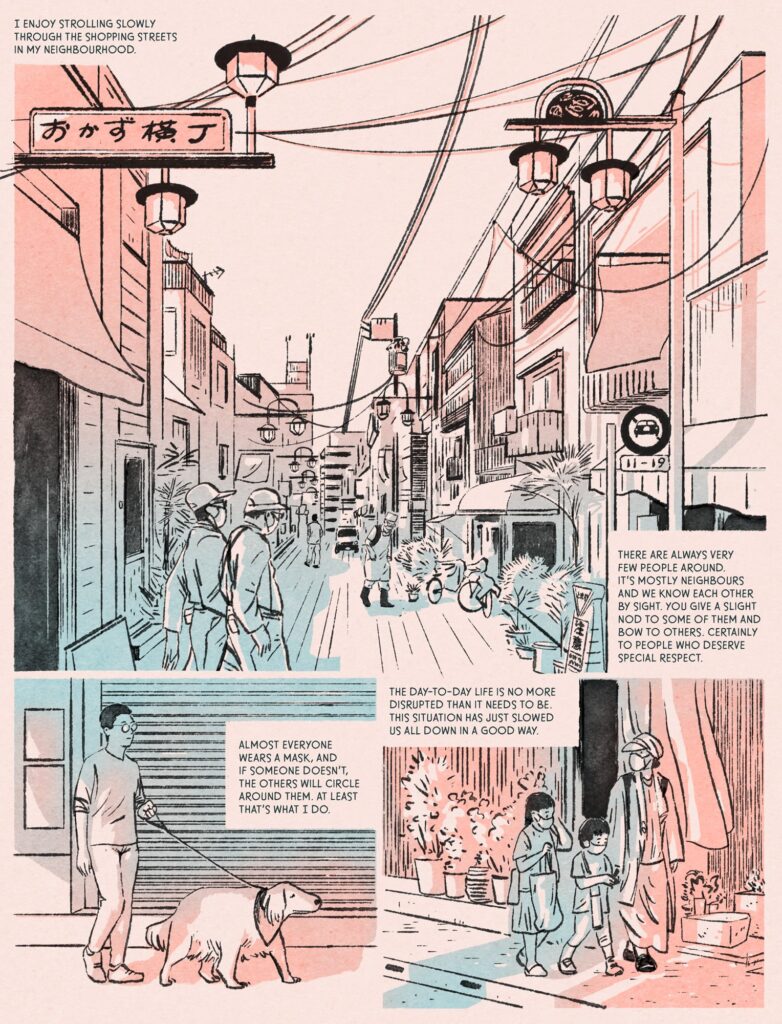

Like a snow ball indeed. When the pandemic hit I was a little bored and decided to start one of my many personal series, something I draw only for myself, which I called The Homestayer, a series of drawings about staying at home. The New Yorker is about people living in New York, and I thought that since we were all at home, it didn’t matter where we lived. We were all HomeStayers. I saw a documentary about people who had to stay at home because of the pandemic, and they were crying because they were stuck at home. I thought, «Why on earth cry? It’s the best thing ever! You have your coffee, your books, your music. Why are they suffering so much?» These people had horrible, depressing homes. So no wonder they cried – if I was in that home, I would cry too!

I realised that there was a negativity about staying at home. I didn’t really understand it. For me, there was practically no change – I guess that goes for most small freelancers like me. So I made these drawings, of people enjoying their homestayer status, to give a positive view of being at home.

And they caught on. People liked them and they got some traction online. Until Handsome Frank (an illustration agency in London) saw them. They called me and said they would like to take me on their roster. I was delighted, because Handsome Frank is one of the main illustration agencies. So they took me on and it brought me important and bigger commissions, the likes of Apple, Amazon, Time, The Guardian, and so on.

My snowball grew and grew. Until last january, when I got an email from South Korea, from Seoul, asking to hold an exhibition of my work. I thought it would be just one room, but no, it’s three floors of a big gallery. It’s more like a small museum. And they wanted to fill it with Luis Mendo, which I found really hard to believe. And that’s what I have been working on for the last few months. I took a few months off commission work and dedicated myself to making the show as good as I could. Now it finally opened and I am so happy…

Congratulations!

Thank you.

But this doesn’t look like chance to me at all.

Nobody believes me when I say it – I haven’t done anything, I just drew in cafés.

(Laughs)

No, no, no, seriously. Everything I have done has been because of my urge to say something. Most of the time it’s unplanned – I just start drawing on my iPad and something emerges. And some things, nobody likes them, they go nowhere. But other things seem to hit the spot and people like them, and that’s great.

But I don’t consider myself good at all, because I’ve been working professionally for eight or nine years, which is not a lot. Professional illustators have spent a lifetime learning the trade. I’m new at this, and I feel like a newbie.

I don’t think they give you jobs out of charity! I’m really tickled by the fact that you do commercial art, but your approach is not commercial at all.

Not at all. In fact, when something is too commercial, I get nervous and the result is terrible. But it’s really important to bear in mind that something has to be commercial. When you have worked in design, you are constantly thinking about the client, about the end consumer, or the reader, whoever is going to consume your work. And you’re always adapting. I am malleable, I can adapt that way – I can draw something that is really serious and very very grownup, but I can also draw something really silly and cartoonish and I’m equally happy. Because it’s the same to me: I’ll do whatever I’m asked to do.

In this regard, I have an advantage over other illustrators who have a very fixed style or their own line, and they find it really hard to depart from that. I have been a chameleon throughout all my life as a designer. I would set up a magazine for an insurance company and the next day a fashion magazine for 15-year-old girls, and a month later a national newspaper. That’s the kind of work I did in the Netherlands.

So I’m used to wearing different hats. And I’m really happy doing it. In fact, I like change, I like leaping from one thing to another. It’s the only way to learn, too. If you already know everything, if you always do the same thing, why get up in the morning? To do the same thing all over again? I’d rather get up and not know what’s going to happen.

The only constant in my work is change.

They did a short documentary about you, in which you talk about how important being constantly learning is for you. How you need new things and learning and to keep growing. I think that’s very clear in your work.

It’s something I’ve learnt from Japanese culture. Do you know this search for perfection that we attribute to Eastern cultures in the West? We say, «Asians do things perfectly». It’s a misunderstanding. The Japanese are always seeking perfection while being fully aware that they will never achieve it. So they improve their processes more and more, they do things fifty thousand times until it comes out really well, but they say «no, no, it’s not good yet». I don’t know if you’ve seen Jiro Dreams of Sushi – how the sushi chef keeps cooking the rice, how he keeps thinking about it. It takes years to learn how to cook rice. Well, in fact Japan is full of Jiros!

I look at my daughter, who’s three, how she folds a piece of paper, and I’m astonished. In her kindergarten, they take naps on the floor, and they have to roll out their own futons. They have a way of doing it, and my daughter comes home and repeats it with towels. She takes a towel and lays it out on the floor, and I’m watching her open-mouthed. When I was three I wasn’t even half as aware of how I did things with my hands.

So this obsession with doing things well, the obsession with improving and perfecting things, rubs off. Here nobody thinks «if it’s not exactly right, that’s okay».

Clearly, you have incorporated this. You have a wonderful newsletter in which you talk about how to keep improving. It’s a bit like the Platonic idea, which you can never reach. But you need to keep trying, because, as you say, that’s what we’re here for.

Right. It’s the path that is beautiful, arriving is not the point. Knowing is much less interesting than learning. Learning is so much more fun!

Another thing that struck me is a Renoir quotation on your website, about the need to see art as something pleasant. Years ago I went to a Picasso exhibition in New York. And they mentioned how Picasso was obsessed with Matisse, who was an artist who focused on pleasure, on beauty, on enjoyment. Picasso thought that Matisse was the only one who did something that he, Picasso, was incapable of – beautiful art in this sense, in the sense of pleasure, of enjoying life, as opposed to the tormented artist shtick. I was thinking that that’s really difficult, and almost seen as shameful, like you’re not a real artist if you’re not tormented.

Years ago, I would buy Spanish records whenever I went to Spain, because I liked Spanish music. But the music they would recommend me in shops was all really depressing. You shouldn’t feel guilty for being happy or liking something, for talking about beauty. It seems to me that many people seem to wallow in ugliness, in death, in blood, in suffering. That has never suited my personality, never.

As you know, I’m the creative director at Almost Perfect, a creative residence that I have set up with Yuka, my wife. We get applications from artists from all over the world who want to come and work in Tokyo for a short period of time. I opened one, and saw death, bleeding eyes, sand being thrown into a girl’s face. And I thought, why, why? There’s so much suffering already in the world, in life. Why do you have to keep hammering it in? I prefer to talk about beautiful things. I don’t mean that you should be drawing Mary Poppins or Barbie, but please, don’t be so depressing either. What’s wrong with being positive?

I think we are at a point in history, in a social discourse, in which, as you say, there’s a certain wallowing in the apocalypsis, in the end of the world. «Everything is terrible, we’re going to hell in a handbasket». And you do art about serious stuff, because you are often inspired by serious stuff. But ultimately it’s about feeling good, there’s always a feeling of wellbeing underlying it.

If you think about it in historical terms, we are better than ever. There’s fewer people starving, fewer wars than ever. Of course, we can fuck things up because we are messing up the environment, and there’s always idiots fucking things up like Putin. But I think, in general, most of us are doing okay.

Moreover, there’s very little discussion about what is being done, the work being done to solve problems. We are aware of the problems, we are working to solve them. We could focus a bit more on that.

Quite honestly, we seem have grown spoilt. Like spoilt children. We have been pampered. My son has been pampered – he has always got everything he wanted. My sister’s children are driven everywhere, they are really overprotected. I think, to a certain extent, that’s the prevailing mindset.

I feel a bit like an old man saying this, but I feel that many people complain over nothing. In fact, in life you have to fight. Because life is hard work and eternal disappointment. And that’s okay. Wanting to achieve things (love, a goal, a dream…) makes you embrace life. If you had it all, life would make no sense.

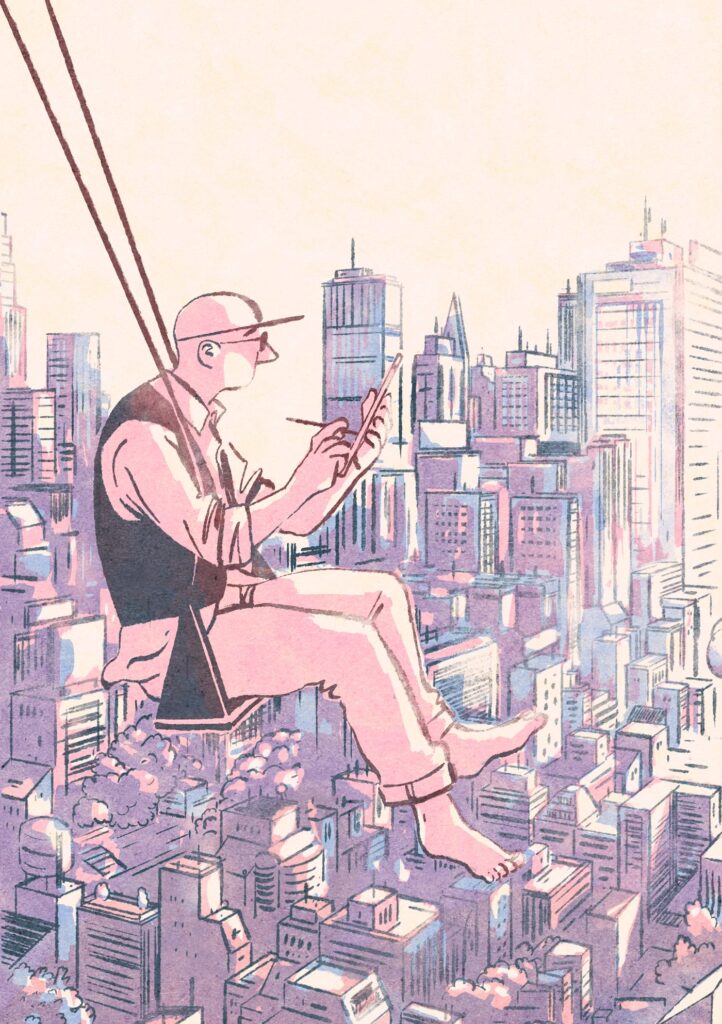

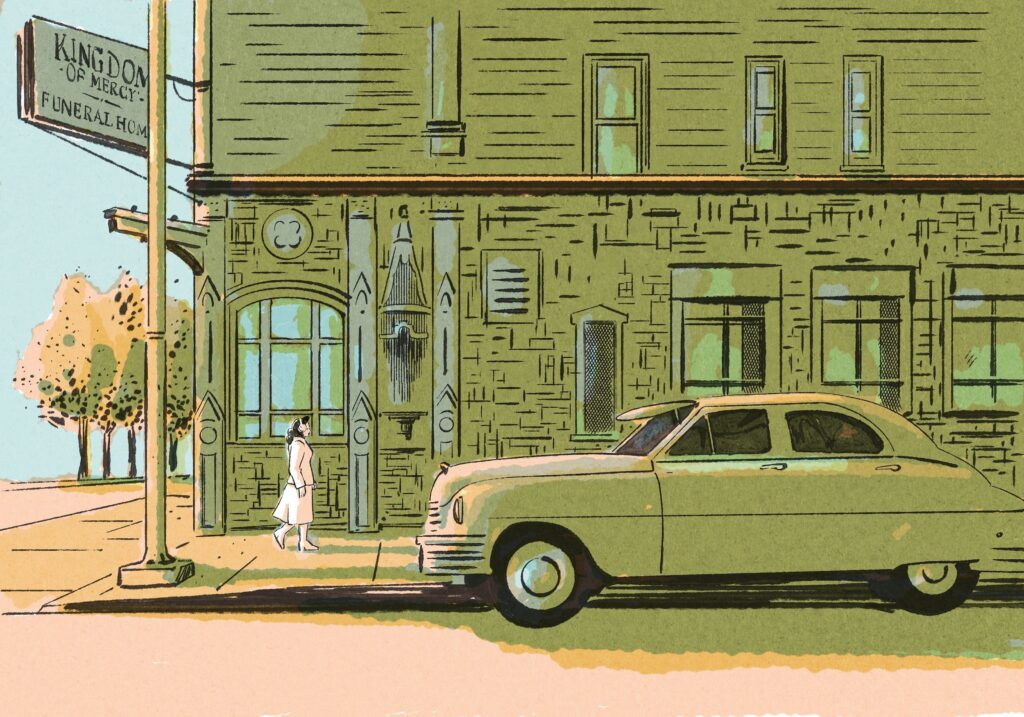

As someone who works with verbal language, one thing that I find striking about your work is how often it is about urban stories, stories in large cities. I find it fascinating how you can encapsulate an entire narrative in one image, how you tell a little story there. With verbal language, it’s one thing after another, one word after another, you start at this point and end at this point. Whereas in art, in an image, all elements are given simultaneously. How can you develop a narrative in images, which are static?

Personally, when I start a drawing, I think in the same way as when I did the page layout for magazines. There’s a hierarchy, which can take different forms – perhaps a large element and several smaller elements, but it can also be a colour, a light focus that attracts attention. That’s like the header. Then a shadier focus is like the introduction, and the rest is like the body of the text. When drawing, I arrange things as I used to do with like the hierarchy of the text in a magazine, only I do it visually. So I work in a very editorial way.

I also use colour and light to make references. I like retro images, 70s and 80s films. So I use certain colours to remind viewers of when they were young, or of an older film. I play with that too.

It’s also what I would do as a designer when I selected a certain font rather than another one, because I wanted to give it a certain feel: more feminine, more classic, more vintage, more shouty, whatever.

In fact, your work often interacts with someone else’s text. And you have designed your own font, Mendo Sans.

Yes, because every time I wrote a text, I wanted to give it my voice. I couldn’t find any font that was sufficiently me. I used Futura, because it’s simple, recognisable and familiar, but it’s not me. So I commissioned some typographer friends and they helped me with all the technical side. It’s very important. Because everything that is graphic has connotations.

For example, in Japan you are officially asked to take a medical examination every year. They send you an envelope to your home. If you do nothing, they’ll send you a second envelope, which will now be orange. And you think «shit, I forgot», because they’re telling you «What happened, why didn’t you come?» And it’s all through the choice of a more striking colour, which conveys the meaning «hey, we’re waiting for you, don’t forget».

Everything is graphic language. For me it’s a no-brainer because I have been doing this for so long, but every decision in design has consequences. And by design I mean everything: how you open a pack of cookies, what colour of tables you choose for a restaurant, how many hooks you hang in a toilet.

It’s a visual grammar, visual semiotics. Everything has a meaning.

Everything.

Particularly in Japanese society, which is highly hierarchical and has very clear social patterns. How do you deal with it? We Spanish tend to be much more spontaneous – how do you fit in?

It’s awful, awful, because I’m terrified for my daughter. Women’s role in society here really needs to improve. Men treat them really badly. I know I said that you shouldn’t complain, but here women don’t complain, they just suffer. Women and many people suffer – men too, but mostly women.

There’s a new wave, which I’m enthusiastic about, a movement of women entrepreneurs who start their own companies without relying on men to do what they want to do. My wife is one of them and I hope my daughter will turn out that way.

I’m lucky because my daughter has quite a temper – she’s practising on us. She’s the boss, and it’s great.

Japanese culture suffers from the tall poppy syndrome – they knock down those who stand out, so that everyone is the same. Even though my daughter will suffer if she raises her voice, I hope she will be confident, that she will take the reins of her life and be responsible towards others and towards herself. That she will have self-respect.

That’s something I don’t like about Japan. For example, when we go to see my parents-in-law, my father-in-law does nothing. He won’t even take his plate to the kitchen when he has finished eating! I tell him, «hey, father-in-law, what’s up? Why not clear the table?» Because I’m Spanish. And then he does take it to the kitchen. But that’s it. That’s what I like the least about Japan, if I’m honest with you.

But we are working on educating him. (Laughs)

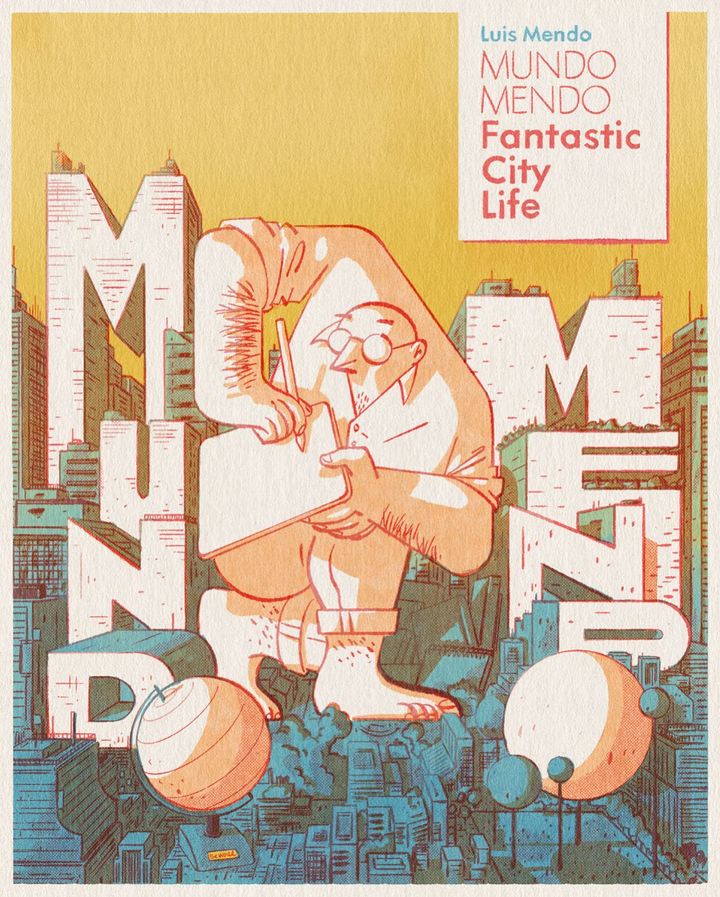

Revolutionary! I wanted to ask you about your alter ego, Mister Mendo.

It’s a bit odd. For this Korea exhibition, they have made lots of merchandising: towels, pillow cases, pens, all sorts of thing. This is really standard in Asia, but particularly in Korea. I was a bit concerned about whether it would hurt my name as an illustrator or an artist.

So I thought I would bring my more commercial stuff under the Mister Mendo brand, and sign my editorial and more artistic work as Luis Mendo. I have split myselt like this to protect myself. I don’t know whether it will work because I’m finding it hard to remain split.

I wish I could have a clone who made my bed while I watched television, though!

The Seoul exhibition brings together your work in the last eight years, doesn’t it?

Yes, that’s why we also called it «Mundo Mendo». It really is all I have. They’ve brought everything out, everything. They have grouped everything into theme rooms which makes it very coherent, and now I feel completely emptied out, but also that I’m about to create a new world.

These last eight years have been like a sketchbook as I learnt, and I still don’t know anything. So I’m delighted that they’re bringing my sketches out.

Now that the show is opening, I want to look forward, take my next step. The exhibition is great and I’m really happy. It’s a sort of milestone for me. A point along the way when you say, well, up to here there was this, and now there will be something else.

I want to see it as a step. I don’t know where I’m going from here – perhaps from the next step I’ll see the sea. Or another beautiful thing.

Could you tell me a little about Almost Perfect?

It’s another project that was like a snow ball rolling down the mountainside. We used to live in central Tokyo and wanted to move somewhere quieter. By chance, we found a house that was a former rice shop, which comprised the shop and the two upper floors where the family used to live. We started living there, and had two floors we didn’t really use. So we thought about setting up a café, a gallery, a coworking space.

Everyone I knew who came to Tokyo would ask me where to go, where they could buy drawing materials and so on. I was a bit tired of having to give this information all the time. So we decided to set up a studio where people could work and exhibit in a gallery, and we could explain things there. And that would cover the rent.

And then Yuka got pregnant, and we saw that was no house for a baby. It’s old, and artists worked there, and you couldn’t have a baby crying – it’s not professional. So we left and rented out the two rooms to creatives. They come, they sleep in one room and work in the studio, and then they exhibit their work in the gallery.

At Almost Perfect we are open to all kinds of creatives, including writers, for a minimum of two weeks and a maximum of six. It’s fun to run, but it takes up a lot of time.

It’s not just for visual artists?

No, not at all. In fact, we have had musicians, biographers, architects, entrepreneurs, decorators, all sorts. They only have to do something that will be interesting for the people who usually come to Almost Perfect. We try to make it something both for visitors and for locals. We’re like a hub, the bridge.

Right. Because you also create community in your environment.

Right. Yuka, my wife, works as a sustainable fashion consultant. I’m an illustrator. And we have a three-year-old daughter, which is a job in itself. So the two of us have 3 jobs. We are also walking the tightrope, doing a balancing act. Almost Perfect pays for itself, but barely. So we are thinking about making it bigger and hiring someone to run it.

But it’s great to see such talented, such enthusiastic people come, and they are so grateful for it. It’s great to see their exhibitions later. People in Tokyo come to see their work and they make friends, they make customers thanks to Almost Perfect. It’s really great.

It certainly is. Is there’s anyhing you’d like to talk about that I haven’t mentioned?

I believe in the value of drawing. We are living in a world in which mathematics and science are the most important thing. People have cast art, literature, drawing aside. Creativity is thought of as game, something for people who don’t make money, something worthless. That makes me so sad. And I think that our society has degenerated because we have come to despise everything that doesn’t make money or wealth.

The other day I heard something really interesting. Yuka, my wife, had set up a sustainable fashion exhibition here in Tokyo. A friend of hers came to see it, and Yuka went to have lunch with her and spend the afternoon together. They went for lunch, had some delicious ice cream – she sent me pictures of the ice cream – and then they went to Armani or Chanel or some shop like that and they tried on dresses. When she came home Yuka said it would have been impossible to pay for the dress, they were all so expensive, but they had a great time. I said: «What would you want the dress for?» She had already enjoyed it. The pleasure is trying it on and spending time with a friend. That’s true wealth, not having the money to pay for the dress – that’s not wealth. Poverty is having to buy a dress to feel good.

I try to teach this to my daughter. Every day, we walk past some flowers – I don’t know what they’re called, it’s a very pretty orange flower that looks like a face. Every day, even if we are late for kindergarten, my daughter wants to take a picture of the flower and draw a face on it using the iPhone. She draws eyes, eyebrows, a nose, a mouth on the flower. I try to go through another street because we’re late, but she’ll say «No, no, Dad, the photo. I want to draw a face on the flower». I have lots of photos of these flowers – and the fact that my daughter insists on doing this, to me, that’s wealth, that’s beauty. We are a bit late for kindergarten, and that’s all right. This is what makes my life rich.

I made a lot of money as an art director, and the only wealth, the only pleasure that gave me was having the savings to come to Japan. But only having money in the bank seems an incredible poverty to me. Being able to draw in a café all day because I had some savings. That, for me, was the real wealth.

Basically, being in life. Paying attention to what is there, to what you are enjoying. Which is what we were talking about before.

That’s it. There’s a water pump where I live, one of these old pumps. You need to push the handle up and down to pump the water out. Pumping water is the highlight of my daughter’s day. She loves pumping water.

I think to myself, that’s so beautiful. And it’s free, it’s free, you don’t have to pay for that. All the truly good things in life are like that. Everything I love and brings me pleasure is free